How a Formerly Incarcerated Man Began San Quentin FF

The Bay Area’s newest film festival has a curious dress code.

“No blue, green, orange, gray or all-white clothing,” reads an email sent to attendees by an event organizer. White is allowed if combined with other colors, but all black is always safe, the instructions continue. Open-toed and open-backed shoes are not permitted.

Rules like that come with the territory when you’re planning the world’s first-ever film festival inside a prison.

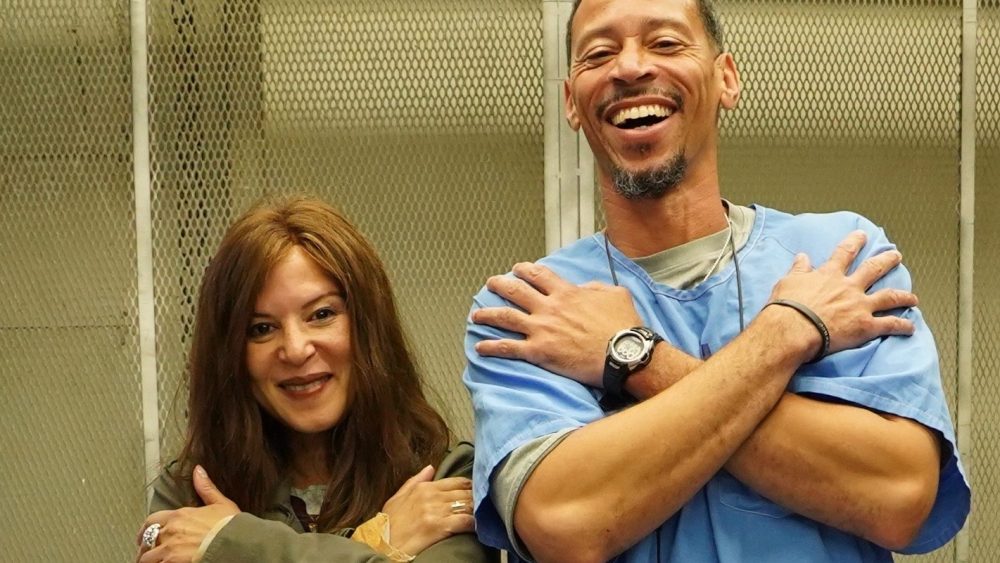

The San Quentin Film Festival, taking place Oct. 10-11 at the San Quentin Rehabilitation Center, aims to help “system-impacted people to be seen, heard and felt,” says co-founder Rahsaan “New York” Thomas. A documentary filmmaker whose career began while he was incarcerated at San Quentin, Thomas directs the festival alongside his close friend, screenwriter Cori Thomas (no relation), whom he first met in 2016 when she visited the prison to conduct research and reporting for a podcast produced by Amazon’s Audible (the project was not released).

“Rahsaan is one of the first people I met there, and he actually changed my entire notion of what prison was,” Cori says Cori, who joins Rahsaan on a Zoom call. “I walked in with very low expectations about the sort of people that I would meet, and I walked out feeling really ashamed about why I prejudged a whole group of people. Because nobody met what I was thinking.”

Rahsaan laughs. “What did you expect?” he asks, though he knows the answer.

“I really thought I was going to meet a bunch of hustlers, and everyone was going to be like, ‘Get me out of here!’” Cori says. “I walked in with my guard up. But except for the fact that everyone was wearing the same uniform, they were anyone you could have met anywhere.”

San Quentin is home to a robust media center that offers access to various production resources, including donated cameras, sound equipment and editing software — but no internet access. Users of the center train themselves with film books and instruction manuals. There’s also San Quentin

News, a journalistic outlet that was established in the 1920s, and more recently, creatives at San Quentin have used the media center to produce short films and podcasts, including “Ear Hustle,” which in 2020 became a Pulitzer Prize finalist.

San Quentin Film Festival co-producer Brian Asey Gonsoulin and “Ear Hustle” host Earlonne Woods alongside Steve Kerr and Alvin Gentry at the annual Golden State Warriors vs. San Quentin Warriors Basketball Game in 2013.

Harold Meeks

The center is an ideal site for projects like the one that brought Cori there, which can change the lives of the men who participate in them. As Rahsaan puts it, “Prior to these opportunities, I was limited to what you could do in prison: Cut hair for a case of soups. Send my son 20 bucks. I was limited to bullshit — excuse my language.” Until the Audible podcast that introduced him to Cori, he says, “I was making $36 a month, minus 55% for state restitution. Amazon paid me $5,000. It was the first time I ever made any real money to take care of my kids from prison.”

After the podcast, Cori became what Rahsaan calls a San Quentin “super volunteer,” spending hours in the media center and bringing work to the incarcerated people she met there. For example, she split the profits from her 2019 play “Lockdown,” which was staged at the Off Broadway Rattlestick Theater, with Lonnie Morris, an incarcerated man who helped her write it. When seeking out poster designs and original music for the play, she turned to artists at San Quentin and paid them too.

Because she believed in their talent, Cori became a trusted mentor for the men who utilized the media center. “People used to give me their writing to please look at, to give them feedback. Somebody gave me a screenplay one day, and I just flippantly said, ‘We should have a festival in here,’” Cori recalls. “Rahsaan happened to be standing next to me. He turned, and he said, ‘Are you serious?’ And that’s the moment I became serious.”

The two soon sat down to write a proposal and begin getting their idea processed through the bureaucracy of the prison system. But the pandemic hit shortly after those first conversations, cutting off Cori’s access to San Quentin for two years and kicking the festival far down the prison’s list of priorities. Crucially, though, it was during that waiting period got that Rahsaan got closer to his freedom.

In early 2023, Rahsaan was released from San Quentin. His work from inside — as a host of “Ear Hustle,” a producer of award-winning documentary projects, a contributing writer for The Marshall Project and more — helped him make nonprofit and entertainment industry connections. Funding for the fest began coming in from organizations such as Meadow Fund and The Just Trust, along with donors Cori met during her years working for Tribeca Enterprises CEO Jane Rosenthal. And Rahsaan got some help from a few celebrity friends.

“I got to meet Mary-Louise Parker, and I got her number. So when we were talking about real jurors and making this a real film festival, I called her like, ‘I would love for you to be a judge for the San Quentin Film Festival,’” Rahsaan recalls. “She said, ‘What? Yes! Matter of fact, let me talk to my friends.’ She rattled off like 10 people, and five of them agreed, including Jeffrey Wright, Billy Crudup, Kathy Najimy and Lawrence O’Donnell.”

“Every Second” is a narrative short film screening at San Quentin from formerly incarcerated directors Antwan Williams and Maurice Reed alongside Reyna Brown.

San Quentin Film Festival

The jury also includes “Sing Sing” director Greg Kwedar and Piper Kerman, writer of the memoir that became “Orange Is the New Black,” among others. But those industry names only preside over half of the festival, a section of short films made by currently or formerly incarcerated people — such as “Every Second,” which centers on a recently released man contending with the reality that he will never be free from his experience of incarceration. The other screening section is devoted to feature-length prison-set movies made by people who have never done time; those have been reviewed by a jury of incarcerated people.

That choice speaks to Rahsaan and Cori’s core belief that incarcerated people should be seen as the authority on what it’s like to live in prison. Rahsaan began making his own films after multiple experiences appearing in documentaries by outside filmmakers. “I’m proud of most of it,” he says, but he’s also seen himself used for the sorts of projects that Cori says negatively influenced her perception of prisons. before she ever visited one.

“Even the films I’m really happy with, at the end of the day, they get the accolades,” Rahsaan says. “They get the paycheck, and we’re still in poverty. I was making 19 cents an hour while I was doing all these documentaries inside. So I want more equity in this industry.”

Rahsaan knows firsthand that access to the arts can truly rehabilitate an incarcerated person. San Quentin’s media center, for example, has a recidivism rate of zero; none of its participants have gone back to prison after release. “I’m having a great life. I’m making more money now legally than I did as a drug dealer,” Rahsaan says with a laugh. “I was exposed to gunfire. I didn’t know about cameras.”

“Healing Through Hula” is a documentary short film screening at San Quentin from currently incarcerated director Louis Sále.

San Quentin Film Festival

So Cori and Rahsaan’s goals go beyond this week’s event. After connecting current and formerly incarcerated filmmakers to potential industry employers at the festival, they plan to extend their work to

other prisons around the globe.

“Our hope is that this is a successful festival so that other prisons will get media centers,” Cori says. “Then all of them can start submitting movies to the festival, and it becomes this worldwide thing.”

“What I would love is to get a budget and do script pitches,” Rahsaan adds, “because I want you to be involved in this even if you don’t have a media center. I would love for somebody to greenlight somebody’s script who’s currently incarcerated, and give them a development deal for $200,000 and break the cycle of poverty for their family.”

So a lot is riding on the inaugural San Quentin Film Festival, but early signs look promising.

“We’re over the amount of people we agreed about with the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation,” Rahsaan says. “Then we got people today asking, ‘Can I get in? Can I get in?’ I’ve never seen so many people want to go to prison before!”

(Pictured at top: Cori Thomas and Rahsaan Thomas at San Quentin in 2018.)