Glowing Tribute to Spielberg’s Composer

From the deep, quickening heartbeat of “Jaws” to the astral opening blast of “Star Wars,” the music of John Williams not only earns its place among the most iconic film scores of all time, but it also proves memorable enough to carry with us out of the cinema. So effective are his themes that to hum just a few notes of a Williams score is to be caught up in the same emotions you felt gazing up at the big screen in the first place, watching Superman take flight over Manhattan or Elliott and E.T. bicycle across the moon.

At age 92, the maestro has received no shortage of accolades — from institutions, admirers and his peers in the Academy — and yet, Williams has long resisted requests to turn the cameras around on him. “Music by John Williams” does just that, featuring extensive interviews with the composer, plus glowing endorsements from directors and musicians who’ve worked with him. It is not a documentary so much as a tribute, a tool for fans designed to celebrate Williams’ legacy without getting too personal or technical in the process.

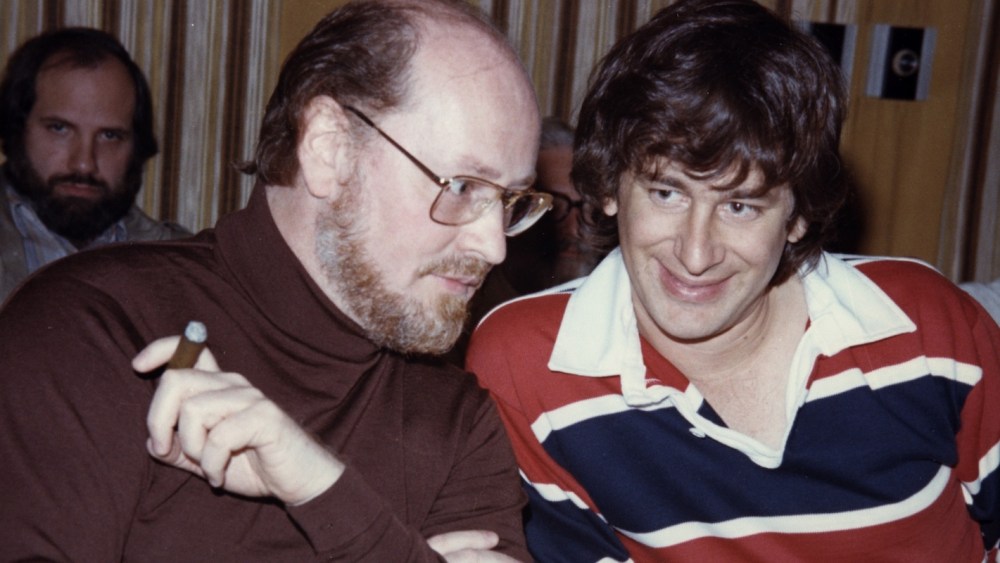

The film’s director is Laurent Bouzereau, whom many will recognize as the guy Steven Spielberg trusts with his own mythmaking, as seen via the “making of” docs on many a DVD. Spielberg appears early and often here, which makes a certain amount of sense, since the collaboration between the blockbuster director and his favorite composer changed the course of both their careers. Early on, Williams sits at the piano on which he first played the ominous two-note “ba-dum” that signals the threat of an unseen shark in “Jaws,” and in walks the director to hug his old friend “Johnny” and share how he felt when he first heard that theme.

It’s a good story, and one that may surprise people, since Spielberg originally enlisted Williams on his previous feature, “The Sugarland Express.” The director had liked Williams’ old-school orchestral scores for two Westerns, “The Reivers” and “The Cowboys,” and wanted something similar for his “Badlands”-like thieves-on-the-run movie. Williams wrote him a folk-sounding score, enlisting harmonica master Toots Thielemans at its center, offering an unexpected, original solution to the assignment.

On “Jaws,” Williams veered even farther from what Spielberg thought he wanted. The director had taken snatches from Williams’ avant-garde and often atonal score for Robert Altman’s “Images” and cut together a temp track. Williams had something totally different in mind, stripping the suspense down to just a few ominously accelerating notes. Would the film still have succeeded without Williams’ score? It certainly wouldn’t have been the same movie, and from that moment forward, Spielberg made the composer a key member of his creative team, counting on the film to come alive during the scoring session. “It’s what I look forward to on every single movie,” he tells Bouzereau, who brings audiences inside several of those recordings.

Such behind-the-scenes stories feel like raw gold for cinephiles, although the documentary doesn’t contain nearly enough of them. We learn how Williams nearly passed on “Star Wars” to write the music for “A Bridge Too Far” instead, and we get insights into the violin-driven score for “Schindler’s List,” which Williams miraculously produced the same year as “Jurassic Park” — a testament to the sheer range of his talent (as well as Spielberg’s). One can find certain commonalities running throughout the composer’s oeuvre, from his knack for crafting indelible themes (the backbone of nearly every Williams score) to the virtuosity with which he expands that catchy bunch of notes into a multi-instrumental symphonic experience.

And yet, Williams never seems to repeat himself — not even in sequels — except in that most musical of ways, by circling back around to the theme (or character-centric leitmotifs, as in “Star Wars”) in order to adapt those core harmonies to a fresh context. If that sounds like gushing, such enthusiasm is entirely in keeping with the film’s tone, as A-list collaborators (including George Lucas and J.J. Abrams), instrumentalists (Yo-Yo Ma and Anne-Sophie Mutter) and assorted devotees (Thomas Newman and Seth MacFarlane) sing his praises.

The film rightly credits Williams with almost single-handedly saving the orchestral film score, a tradition on its way out as synthesizers, jazz and pop songs came to dominate soundtracks. It would have been great to see how Williams works, which is only hinted at here, as he transcribes a few ideas by hand and shares a page of five-note combinations that could have served as the main theme to “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.”

Despite having unprecedented access to the legend, Bouzereau doesn’t go especially deep into Williams’ process or personal life. The son of a jazz drummer, young Johnny landed his first film-scoring gig not by leaning on family connections, but via his Air Force service. Williams’ early career gets only cursory attention, even though he already had two Emmys (for “Heidi” and “Jane Eyre”) and the first 10 of 54 Oscar nominations (including a win for “Fiddler on the Roof”) by the time “Jaws” came along.

That just goes to show that “Music for John Williams” is intended more as a greatest-hits reel — the documentary equivalent of a flattering coffee table book — than an attempt to better understand the man. The film does mention an early tragedy: the unexpected death of Williams’ wife Barbara Ruick from an aneurysm in early 1974. And it touches on a tricky moment in his career, when he resigned from conducting the Boston Pops a decade later — but only for a time. While that incident reminds how film composers aren’t taken as seriously in the classical music community, Coldplay frontman Chris Martin calls Williams “the biggest pop star ever.”

The movie samples a few of Williams’ non-film works, though there can be little doubt that it’s the magic he brought to movies — and his collaborations with Spielberg and Lucas in particular — that will ensure his music is still performed centuries from now. In fact, as we’ve seen the original “Star Wars” trilogy age, it becomes increasingly clear that Williams’ score may be the ingredient that proves the most timeless, still to be appreciated long, long from now in … well, you know the rest by heart.