‘A Complete Unknown’ Director James Mangold on Making Bob Dylan Biopic

Something is happening here and, given the hoopla over “A Complete Unknown,” probably even Mr. Jones has an idea what it is: Bob Dylan mania. Thanks to James Mangold’s new film, America is currently experiencing a spike of collective fascination with Dylan that probably hasn’t peaked quite this high since 1965, when the events of the biopic wrap up.

Thankfully, “A Complete Unknown” has turned out to be a thoughtful treatment as well as a crowd-pleasing one that, against most odds, seems to be equally bowling over deeply Dylan-informed boomers and younger audiences that might have Timothée Chalamet as their first point of entry into this world. (The film has accrued a 96% audience approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, and when Cinemascore pollsters asked “How does it feel,” the response was a solid A grade.) As a filmmaker, Mangold (“Walk the Line,” “Logan”) doesn’t try to solve the mysteries of Dylan for moviegoers. But it appears he’s given them something they like even better than easy psychological tropes: electricity.

Variety talked with Mangold about the challenges in structuring the screenplay (which he took over from initial writer Jay Cocks); what happened when he spent 18 hours personally talking with Dylan; his direction of award-contending performances from Chalamet, Edward Norton and Monica Barbaro; and, surprisingly, how Pete Seeger was as much of a youthful hero to him as Dylan.

For some of us who didn’t think there could ever be a convincing, realistic portrayal of Dylan on screen, and one that works for people as a movie, there’s a feeling that you’ve pulled off the impossible.

Well, I think some people were so convinced it’s not possible, they’re looking at the movie and even now remain convinced it’s not possible. Even if it might be possible, they just can’t open their eyes. Sometimes people say they want more of Dylan’s secrets — but then, also, say they don’t want a standard biopic. It’s like, pick (criticism) A or B! But ultimately, it’s really gratifying, the reactions that so many people are having.

It was puzzling, how to make a movie about this particular fellow and that world. And my feeling was to just refuse to acknowledge this kind of enigma stuff. Like, just make the movie, let the events happen and let the audience absorb what they want from it. There’s an interesting level to me where it’s like: How much of an enigma can a man be who’s released 55 records? How much more do you want? He has given us more personal output than almost any artist in history. There’s so much personal poetry that we’ve been exposed to that it’s hard to understand what more he’s supposed to give us that will somehow close the circle for someone.

There definitely are fans who don’t want him overexplained, and were afraid that, if anything, you were going to spend the movie trying to explain or justify what makes Dylan tick.

It’s something I’ve grown allergic to. There’s a kind of standard structure in movies we’ve seen a lot of times, which is: Hero’s carrying a secret; hero struggles to keep the secret down; hero fares badly because he’s hiding something. Come therapy with Judd Hirsch, Tim Hutton reveals the secret, or Matt Damon reveals the secret. “Citizen Kane” reveals the secret, and we now understand! That’s a very sensible meeting of Freudian psychology and dramatic structure. But I also think it’s a little bit too easy, or it’s gotten too easy. And I certainly didn’t feel like this particular character, who I got to also spend time with, would lend himself to that kind of a personal revelation.

As you mention, you did get Dylan to consult on the script. And when people read about that, or saw that his manager is an executive producer, there was a bit of an assumption on some people’s part: “Well, this is gonna be a hagiography.” If there’s anything most people who’ve seen it now would agree upon, it’s that it does not play out that way.

Well, when I came on, I definitely felt like Jay Cocks, who preceded me as a writer, had his hands tied a little bit. He had written some beautiful stuff that I made sure made it into the film. because it was just exquisite work. But there was a level where the script was skipping the early years. It kind of started with Woody (Guthrie, whom Dylan first sought out in 1961) and then went all the way to 1964 almost immediately. I really felt that there was something to seeing the stages of Bob transitioning, but also the relationships, romantic, sexual and otherwise, with the women in the movie. And that was what that trip-wired Bob’s management team feeling nervous about what I was doing when I came on board to the material.

And COVID hit, and then I got a call from (manager) Jeff Rosen saying COVID had canceled Bob’s tour. Given he didn’t have anything to do at the moment, (Dylan) said, “Let me read this script that’s got you guys worried.” And then he read it, and he liked it, and that changed everything. That then instigated the series of meetings with myself and Bob, and Bob read the movie you saw. I didn’t think he had an issue with how he was being depicted, because I think that he saw it as essentially: I didn’t have an agenda, and I wasn’t picking a side. From what I sense being with him, that’s the most important thing — that there’s a neutrality that lets everyone figure out what they think from the circumstances that happened.

I have to wonder what Dylan is thinking when he’s reading the script and — assuming this was in it at the time — it gets to what is probably ithe biggest laugh line in the movie, which is Joan Baez saying, “You know, you’re kind of an asshole, Bob.”

Yeah, yeah. I wrote that. But I had many points like that where I thought he was gonna flag things. I wrote this thing where he goes, “You know, people ask where the songs come from, but they don’t really want to know where the songs come from. They want to know why the songs didn’t come to them.” I was sure that was something he was gonna put a big X through, and he didn’t.

I have a lot of empathy for him, to (A) have that kind of work channeling through you at that age, and (B) have so many people wanting shit from you so quickly. And I’m not sure his comportment of himself was designed to make himself into some kind of prophet. I think he kind of took advantage and played the way that the music was playing… I don’t mean the literal music; I mean the way the kind of public relations music was playing.

My take on his being a fabulous and telling stories of the carnival and traveling the Dakotas by rail: I took it as just a young man’s wish, that instead of being a middle-class kid and son of a hardware store owner, that he had a sexier story. And that he mentally told himself that story enough that part of how he made the work was believing that story and almost playing a role in that space. That all made a lot of sense to me, seeing him more as a dreamer than someone who was trying to fuck with everyone. Being a director of actors may have been an added benefit (in viewing it that way).

Also, my own observation was just that he’s a private person. That he had the peculiar contradictions of his own personality; that he had a talent that put him in the spotlight; and he loved to use that talent and to share his music. But the other aspects of being in the spotlight may not have been something that he was genetically or behaviorally predisposed to handle in a kind of standard, professional way, and especially at that young age.

You’ve described how you had an initial meeting with Dylan, and he asked you what the movie was about, and in being asked that, you had kind of a eureka moment. You told him that you saw it as being about a guy who’s sort of suffocating in one environment moving on to the next, starting with his leaving Minnesota at the start.

It starts with suffocating and then running, and rebirthing or building anew. And any casual observer of Bob Dylan’s life can see that that has been something that’s happened more than once, not even in just the period that I chose to depict in this film. But that’s very much the reason, coming from that talk with Bob, that the movie opens with him at the station, hitchhiking into New York, and ends with him on the back of a motorcycle, riding away. The arrival at the opening is a departure from the world he left, and the departure at the end is an arrival to a new world and, in a way, a new period of his life. That to me was really clear, that cyclical, almost musical-ballad-like pattern in his life.

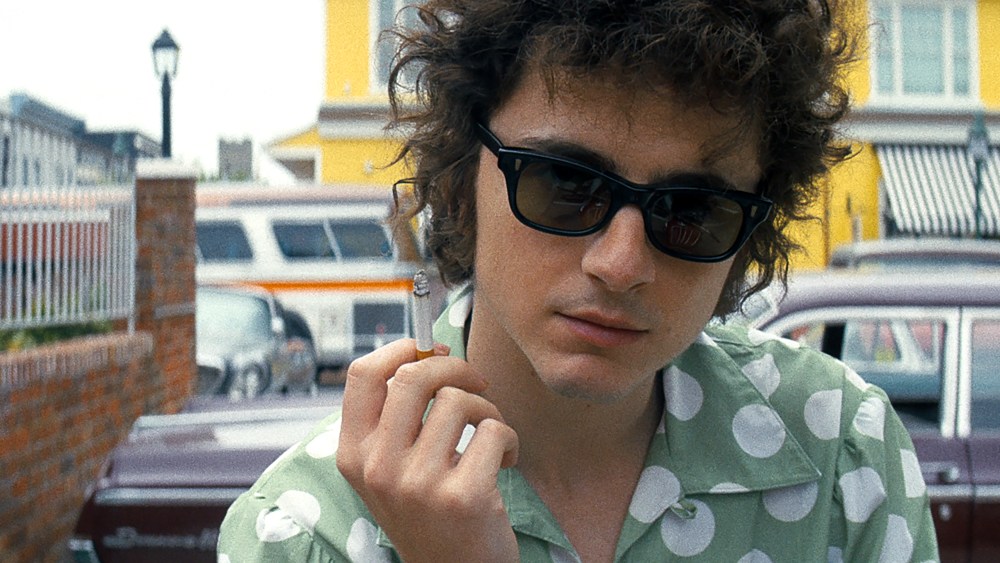

Director James Mangold and Timothée Chalamet on the set of A COMPLETE UNKNOWN.

Macall Polay

So you felt like you understood that bookending for yourself when you were talking with Dylan. But what was the initial draw for working on the project, before you totally figured what it was really about for you?

There’s a very obvious thing where you’re just getting a chance to tell a story about someone. And if it creates so much anxiety for people that you’re telling a story about this person, you must be onto something, because there’s some kind of incendiary quality to the character that is value-added already. Then to add to that, the story itself, whether it was about Bob or not, is about things I’m very interested in, like tribalism in the arts or in philosophy. It’s about how people get so locked in to a dedication to, in this case, what folk music is or isn’t that it becomes an act of disloyalty to play with a band. It’s also about limitations that feel arbitrary, or that kind of theology, if you will, that is imposed on an artist that might cause an artist that has contrarian impulses or broader ambitions to act out against it.

My way of making a movie, both as a writer and as a director, is to kind of really focus on the deeply personal — the local, if you will — and to really not get distracted at all by the large themes, like changing music and realigning the dynamic and cultural shifts. None of that is what was driving those characters, in my opinion — or at least it couldn’t be in a dramatization. I see Newport ’65 more as a kind of Thanksgiving dinner gone amuck, with family issues that have been brewing for several years getting brought to a head. It happens at Thanksgiving because everyone’s assembled and there’s one dinner, and it puts a lot of pressure on everyone to get along and comport, and those few boundaries and behavioral expectations automatically will produce someone who can’t. And then things blow up.

I felt that Bob’s natural growth as a musician was utterly sensible. I mean, as he explained to me, and as all the texts and references I could find validated, he never was only a folk singer, or thinking of himself with the dogma of what is and isn’t a folk song, ever. He had tremendous success in the arena of folk — artistic success; I don’t just mean financial or popular — but that still doesn’t mean it was the form that he wanted to work in until he died. The form wasn’t the point for him; it was just the canvas. And at the second he wanted to paint on a different canvas, which is of course his option, that was suddenly challenging for others who were more dogmatic about the way they thought about what their mission was. And he had a different mission from the very beginning. It’s what I tried, in a very mundane way, to touch upon in this early scene with Pete and Bob in a car where they’re listening to Little Richard on the radio, coming from entirely different places. Bob’s just patiently listening and really offers not much of an argument besides saying that sometimes drums and a bass sound good. But they’re not in the same place.

There’s wonderful nuance to the way Pete Seeger is treated in this film. It goes beyond the basic expectation that you are too intelligent of a filmmaker to make him the villain of the piece.

No, of course not. He’s filled with love. You could say he’s an antagonist by the end, or one of them, but the word antagonist doesn’t mean bad guy. It just means someone with goals that are in conflict with the protagonist. You know, I don’t let people on my sets — no matter what kind of movie I’m making, even if I’m making a Marvel movie — talk about bad guys and good guys. You know, Mads Mikkelsen [who appeared in Mangold’s previous film, “Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny”] doesn’t believe he’s playing a villain. He believes he’s playing a guy who wakes up and is trying to make the world better every day. That’s anyone’s actions. Darth Vader thought the same thing, that he’s doing the right thing. They might have very misguided and psychologically twisted — in those cases — reasons for doing those things, but they believe they’re doing good.

And on a much more muted scale, of course, Pete Seeger has been a powerful voice for positive things in our world, whether it’s cleaning up the Hudson or fighting for civil rights or against war or for the poor and disenfranchised. This has been his life, even more so maybe than music. The mission was bigger than the music for Pete. And for Bob, it’s music. It’s about the song, and the mission is… Well, I can only make my observations. The mission is less important. The song is an offering, and people can decide what mission they want for themselves. That’s really my perception of things.

But, you know, I grew up really inspired by Pete Seeger. Pete Seeger sang in my mother’s camps when she was in the Catskills in her youth. I listened to Pete Seeger records as much as I listened to Bob Dylan records when I was a teenager. And I played banjo, inspired by, as a combo, Pete and Steve Martin, of course, who are both high school heroes. But I have no problem feeling like the movie doesn’t make a judgment about any of these people. They’re all wonderful, in my opinion, in their own unique ways.

James Mangold attends the photocall for “A Complete Unknown” at The Curzon Mayfair on December 16, 2024 in London, England.

Getty Images

Reading the great Elijah Wald book that was a source for your movie (“Dylan Goes Electric!: Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties”), you get caught up in the different dynamics that are happening and producing great music. You can love that Dylan is frustrated and needs to break out and is reinventing himself and creating new sounds — while you can still also love all the different factions of the folk scene that he was leaving behind.

Absolutely. I hope the movie plays that way. I love Joan Baez and I love Bob Dylan and I love Pete Seeger, and again, like a Thanksgiving dinner, I don’t need a villain. I don’t need a heavy in the movie. I think that if you have characters whose goals do not all coincide, yet they have tremendous affection and they need each other for different reasons, that becomes a unique thing.

Also, Pete Seeger found himself with what is a common organizational challenge that we find in other aspects of show business, if maybe not so often in the folk world. This was that the talented figure who he helped bring into the spotlight did exactly what he had hoped, which was grow the dominion of folk music exponentially. With that growth — like in any good story, Shakespearean or otherwise — came a sense of autonomy and power for that young man. And with that came a sense of wondering: Am I only here to raise the fortunes of folk music, or am I here to express myself? And those two things were not in alignment. And at that point things get interesting. I think what’s so interesting and subtle in what Edward’s done in the film is, you have a character who is by nature so committed to mutual understanding and finding a way through, but he can’t quite untangle himself from the fact that his relationship with Bob has become somewhat transactional, and that he needs him to do specific things to further institutional goals.

Edward Norton and Timothee Chalamet in ‘A Complete Unknown’

Searchlight

That becomes not only uncomfortable for Bob, but I think what’s really beautiful to watch Edward do is play how it’s uncomfortable for Pete, meaning that he doesn’t like that he’s in this position. He suddenly is playing the role that the judge was playing in his trial in the opening five minutes. And who wants that? Certainly not Pete, but he doesn’t know a way. He’s trying to find a way to close the circle and see if Bob could even just hang on for this one more show, and not get in a fight at the table in front of grandma this year, and then go do whatever you need. And I feel like that was, at least in the writing process, a much more knowable way to write and try to understand where everyone was trapped.

Edward had this idea of using that oft-told parable that Pete liked to say about the baskets and the seesaw, as a kind of last-ditch way of trying to talk Bob into kind of just eating it for one more year. And I had this idea about him saying “You brought a shovel,” kind of complimenting or flattering Bob into kind of “Maybe you could just use that shovel one more time, and then we’re good.” Then that’s it! But in show business, that’s “We just need you for one more movie” or “We just need one more album out of you.” Then they want another one, you know? So, the reality is, it’s very hard for the folk movement to let go when there’s no likely successor who’s going to offer them the kind of prestige and notoriety and attention that they’ve gotten. And when all the power is in one man’s hands, namely Bob’s, everything has become so asymmetrical that Bob becomes a bully if he basically doesn’t do what they want.

And in ways I felt real compassion for Bob’s character in this situation. He is kind of in a jam. I mean, could he have skipped playing electric there? Certainly. But in a way, I think it was a kind of acting out. I mean, even Bob now, looking back, isn’t quite sure why it all went down the way it did. We’re talking about what a 23-year-old man did. And how many of us looking back, at a ripe age like we’re at, can understand the rationality of everything we did when we were 22, 23 or 24 and know what compelled us?

I say this only half-kiddingly: You already have a good start now on what could be called a Bob Dylan or Johnny Cash cinematic universe, bringing Johnny Cash as a character into this film. A lot of people watching are probably wishing there could be a Joan Baez movie too, and a Pete Seeger movie.

And a continuation of the Bob story into Woodstock. I mean, there’s so many things you could do. To me, that’s what any good movie, fiction or nonfiction, should do — it should have its sights specifically on the story area in which, thematically and otherwise, the characters come to a kind of momentary sense of resolve or turning of the wheel, as things have changed and a new story is about to begin, even while this story is over. And that was what I saw. When you asked me what got me so turned on to get involved, that was it. I didn’t know exactly the story and I hadn’t had the moment of describing his kind of leaving, coming and then leaving again as a kind of pattern. But I did see it as a fable in and of itself that was also, much more broadly than being about Bob, about genius itself and how we all deal with it.

Certainly a real inspiration — I even shared this with Bob — was this idea of kind of using “Amadeus” as kind of a template for myself. Instead of trying to crack him open, the idea was to see the effect that he had on others — which was why I justified to his management team and then ultimately to Bob why I felt it was important to bring all these characters in much more fully. It was because I think that we will understand a lot more about him in an interesting or less cliched way if we are experiencing it similarly to the way Peter Shaffer structured “Amadeus,” where you’re not kind of explaining where Mozart’s music comes from, other than knowing he’s been a child prodigy. You’re understanding more so how the presence of that talent and the enormity of it has an effect obviously on Salieri in that movie in a very foregrounded way, but others, too — the king and the court and the public and his wife. There’s a way to come at a story from that direction, where structurally you free yourself from having to necessarily advance the story in terms of kind of personal revelation on the part of the protagonist.

Timothée Chalamet and Monica Barbaro in A COMPLETE UNKNOWN.

Searchlight

To ask about Monica as Joan, because it seems clear she is going to be a star, or a bigger star than she is, because of this… Joan is so fascinating, and like many people, I watched the recent documentary on her, and after all the decades of thinking of her as Saint Joan, you’re reminded that she was young and hot, in pretty much every applicable sense.

And formidable. The most important thing that I thought Monica has in and of herself is kind of personal power and gravity. There’s a kind of “one of the boys” quality to Monica. She’s beautiful, but she’s not fragile, and she’s not easily off-stride, and there’s a kind of gravity in her for a young woman. I thought that was also, as an energy, going to bring tremendous challenges to Timmy in their scenes. because it was gonna be the one person who wasn’t gonna kind of tolerate his shit… his shtick, if you will.

Monica has mentioned that she talked to Joan on the phone, so I’m wondering what Joan’s attitude was about being portrayed. Even now I think we’re fascinated by how she thinks back on those years and thinks about Dylan, and it seems like this ongoing combination of bewilderment and bemusement. And, still, admiration, of course.

Yeah. But it can be all those things. I mean, the reason you can’t find one word is just, like any of us, we can’t find one word to encapsulate or bracket people we were intimate with and had many adventures with, and the frustrations and conflicts and loves and all sorts of experiences. It’s not simple. You can’t unpack it and say it’s one thing. And I think that’s the number one job I have as a writer. And also helping the actors understand they don’t have to play one idea. They can play three ideas! Because these are adult relationships and they’re complex. You can admire someone’s talent and find someone charming. You can also be kind of falling in love with them, but not be able to find your way in. You can also be extremely self-possessed and not even be comfortable with the idea of falling in love with someone because it’s a loss of your own autonomy and/or power.

What’s so interesting with Joan and Bob is, they’re in many ways equals — talented in different ways, but both supremely talented — and that creates another kind of energy between them, which is when they’re getting a groove together, it’s exalted. And when they fall apart, it’s really hard. And it’s kind of these highs and lows, which is what we tried to write and what I felt like they played so beautifully.

Joan Baez must be OK with the movie, if she was talking with Monica about the role?

Yeah. I mean, I never want to put words in anyone’s mouth, but she was really helpful to Monica and encouraging. And I think the thing that meant the most to Monica was that Joan told her, “I was hoping you’d call.” You know, Monica was terrified (about initiating the call). And, I mean, justifiably, because it’s like, what’s gonna happen? It’s always scary to make a call where you don’t know how it’s gonna go, right?

Did you have a philosophy about directing the vocal musical performances. It seems like with “Walk the Line,” you weren’t worried about having Joaquin Phoenix sound exactly like Cash. And maybe you were or you weren’t here. But you have a film where some people say that if they’re listening to the soundtrack, there are moments where they can’t tell the difference. So I’m sure if Timothee ended up being that good at doing Dylan, you don’t wanna say, “Hey, it’s too close. Make it less like Bob Dylan.”

No, but I think Timmy always felt like it wasn’t exactly (that close), and so did we. I mean, if people think it sounds exactly like Bob Dylan, that’s cool. But that was never the plan. And in either movie we’re talking about, it wasn’t like I wanted them not to sound like the person they’re playing. It was much more a different goal, which may make me sound slightly methody or artsy-fartsy myself. But a great film performance under the microscope of a lens in closeup cannot be all affected. It won’t survive the scrutiny of the lens — meaning that if it’s all affect, if it’s all attributes and what you’re doing to your voice and how you’re using your hands, that’s all great, but you have to bring a piece of yourself.

And Timmy got that. He’s playful and he’s quite brilliant, and sharp as a tack. And some of the scenes of the movie are improvised. I mean, it’s not dialogue that Jay or Iwrote, it’s dialogue that the actors are finding, and that’s because they’ve found that place where they’re bringing themself and meeting the person they’re playing and braiding the two together. That’s what I’m interested in, because that’s what withstands the scrutiny of the lens, that kind of X-ray vision that a movie camera has when it gets up close.

Elle Fanning, Boyd Holbrook, Monica Barbaro, Timothée Chalamet, James Mangold pose with Chalamet and Mangold’s Visionary Tribute awards for “A Complete Unknown” at the 34th Annual Gotham Awards held at Cipriani Wall Street on December 2, 2024 in New York, New York. (Photo by Kristina Bumphrey/Variety)

Variety via Getty Images

Of course with domestic situations, you’re using your imagination more than you would for public things or studio moments that Dylan fans have actual transcripts of. But having read the Wald book again, there are definitely passages where we can see you caught a momen, and were able to turn that into something visual or dramatic.

Right. And there was other stuff I got elsewhere. I mean, I was voracious. It wasn’t only Elijah’s book. It was letters and writings and conversations and interviews and anything I could get ahold of. And then, you know, you’re talking to someone who also has spent five days and probably 18 hours talking to Bob about things, so just imagine. Like, we’ve now talked a half-hour; just imagine that times 36. You talk about a lot of different things — the macro, the micro, the granular and the broadly philosophical. And you get a lot of little stories. You know, Bob told me the stories of (Albert) Grossman being kind of always nervous about the Chicago mob coming after him, and how he would carry a pistol. You’d get all these little tidbits of stuff that you’d use, that all seemed to fit in place in terms of this wonderful menagerie of characters — all of them, not just Bob.

The other thing I got from Bob was tremendous affection. This may have been a Thanksgiving that blew up, in my lame metaphor, but there was also love among these people that carried on. There’s no lack of admiration on Bob Dylan’s part for any of the characters in this movie. He looks at them all with a wistful admiration, and adoration and affection. It’s just that things kind of went upside down and sideways for a while.

You conflate a few things. Like the cry of “Judas” from the audience, which led to Dylan’s response — that famously was recorded at a later show in England, but you had it at Newport because you felt it important to have that in there?

Because I felt like it would be a double-beat, doing the English concert and Newport, Jay and I tossed it in there (at Newport). But in movies, you’re trying to do… We’re not a Wikipedia entry. We’re we’re trying to capture the truth of a feeling, of the characters and the relationships, and that’s much more the supreme goal. Obviously I don’t know which song Bob wrote sitting on the floor or on a bed or at his desk, but you take a leap. And he read these depictions and didn’t have argument with them. It could be that maybe he doesn’t remember, like I don’t remember where I wrote something in my own modest way when I was 23.

But the biggest kind of truth test for me is just that you’re trying to kind of carve out how much all of these people are wonderful. I love them all. I hope the movie conveys that I adore this world — not just Bob — and that the fracture that happens isn’t because I picked a side, but that it’s just like a Tennessee Williams play or anything else. It’s just a fracture that happens among people who love each other when they all are growing in different directions. And it happens to be on a public stage, because that’s where they live. But it’s analogous to all our lives.