A Sobering Brazilian Political Doc

For opponents of former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro — which is to say, among other things, opponents of anti-Indigenous discrimination, deforestation, abortion bans, institutional homophobia and COVID denialism — his loss in the country’s 2022 general election was a relief, but hardly a new dawn. The presidency may once more be held by liberal veteran Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (popularly known as just Lula) of the center-left Workers’ Party, but the demographic shifts and political machinations that enabled the recent far-right takeover still cast a long shadow on a nation beset with economic inequality and social unrest. “Nothing is hidden that will not be made manifest,” says Petra Costa, pointedly borrowing from the Book of Luke, midway through her compellingly impassioned new documentary “Apocalypse in the Tropics,” which rakes with a heavy heart through the recent past while casting an anxious eye to the future.

The heart-on-sleeve expressions of shame, fear and tenuous, glimmering hope that recur throughout “Apocalypse in the Tropics” will not come as a surprise to any viewers who saw Costa’s previous doc, “The Edge of Democracy” — to which her latest serves as a clear bookend. Released in 2019, in the immediate wake of Bolsonaro’s election victory and while Lula was still in prison on false corruption charges, that film considered in depth the reasons behind Brazil’s significant tilt to the right, and regarded the new administration with openly voiced concern. A festival hit that nabbed a high-profile Netflix release and an eventual Oscar nomination, “The Edge of Democracy” laid the groundwork for this follow-up — premiering out of competition at Venice, with Brad Pitt among its bevy of exec-producers —to similarly connect with audiences.

Five years and one global pandemic later, Costa may be glad to speak of Bolsonaro’s tenure in the past tense, but she’s not done analyzing its origins and implications for the country at large. For sibling works released in highly contrasting political climates, “The Edge of Democracy” and “Apocalypse in the Tropics” are notably aligned in their outlook and approach. Which is not to say they share the same talking points. The bulk of the new film, as hinted at in its Revelation-referencing title, is centered on a social phenomenon that Costa admits she under-investigated in her last film: Brazil’s extraordinary turn toward evengelical Christianity, a movement that now accounts for over 30% of the country’s population, up from 5% just 40 years ago.

It is, Costa notes, one of the swiftest religious shifts in history — the kind of seismic demographic makeover that can’t be confined in its influence to one side of the church-state divide. Have been raised secular, the filmmaker confesses her ignorance of Evangelical tenets, and her naïveté as to how they would bleed into Brazil’s social fabric. She decides a close reading of the Bible, and the New Testament in particular, is in order — though the further she delves into scripture, the more she concludes that Brazil’s foremost Evangelical influencers aren’t guided by the word of God, but the very earthly pull of capitalism.

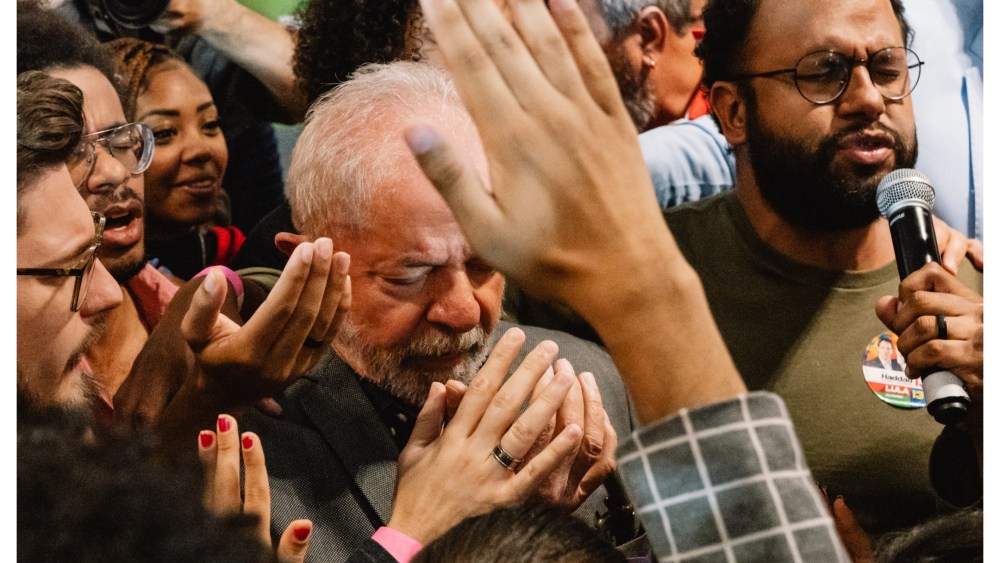

The key person of interest in “Apocalypse in the Tropics” is thus not Bolsonaro, nor Lula — though Costa, an intrepid and disarming interviewer, gets some insightful face time with the latter, a traditionally Catholic-raised man who had to tactically include some gestures to the Evangelical base (including a promise not to change abortion law) in his recent presidential campaign. Rather, it’s Pentecostal televangelist Silas Malafaia, a self-styled political puppeteer with rigidly right-wing beliefs, who is presented as the charismatic crux figure of Brazil’s new populist politics — more influential and more enduring than the individuals he endorses as suitable conduits for Evangelical thinking in Brazil’s parliament and supreme court.

Malafaia is an undeniably magnetic figure, even as he skates on the edge of outright hate speech in his surprisingly generous interviews with Costa, arguing for ultra-conservative Christian principles (including zero tolerance on homosexuality and abortion) as the actionable will of the Brazilian majority. Leaving aside the self-evident counterpoint that Evangelicals aren’t yet a majority faction, Costa instead challenges him on the definition of democracy itself: Shouldn’t it entail the protection of minorities regardless of what the masses want? No, he replies flatly, as if amused by the very idea. “I couldn’t reconcile how the same Jesus who preached love and forgiveness could be used to justify a government with such a lack of empathy,” Costa observes in voiceover. Self-justification doesn’t come up much in Evangelical politics, however: When you profess God to be on your side, you neither have to explain nor compromise what you stand for.

Even with the left ostensibly back in power, Costa wonders how far Brazil might be from becoming a theocracy. Artfully assembled and divided into Biblically-titled chapters, with classical religious imagery used in ironic contrast to Malafaia’s graceless media bluster, the film backs away from the overtly personal narration of its predecessor, in pursuit of a bigger picture. Costa’s archival research takes her to the considerable influence of American superstar preacher Billy Graham, whose Brazilian stadium tours did much to seed Evangelicalism in the general population — and which, she states, were part of a U.S. anti-Communist drive to counter the then-growing leftward slant of Brazilian Catholicism.

Back in the present day, her gaze switches to a hard-up, disenfranchised-feeling public that is highly suggestible to faith-based rhetoric. In the run-up to the 2022 election, she speaks to a single mother, working as a cleaner, who admits that she approves of Lula’s policies: “I’d vote for him, but the Gospel influences my vote.” The Gospel, in this case, is Malafaia, who’s a staunch advocate of prosperity theology that benefits him far more than it does any working-class Evangelicals.

This fusion of religious fervor and party loyalty can be exploited to destructive ends, as seen in the film’s startling, climactic depiction of the January 2023 riots that followed Bolsonaro’s election defeat — where, stoked by the president and Malafaia’s consistent rallying cries for “military intervention,” a mob of incensed Bolsonaro voters crashed and trashed the Congress buildings in Brasilia. The parallel here to the Trumpist storming of the Capitol two years before is so blatant that the film resists commentary: It should be clear to international viewers that this cautionary tone isn’t directed to one country alone.

Such drastic actions, suggests Costa, are the perpetrators’ own interpretation of the Judgment Day violence preached in some interpretations of the Book of Revelation. As her camera gazes around the vandalized beauty of Brazil’s once-gleamingly modernist, future-minded National Congress Palace, we’re left to wonder if the apocalypse has already come, and if so, what happens next.