Captures Just the Way He Is

When it was announced that this year’s Tribeca Festival would open with the premiere of the HBO documentary “Billy Joel: And So It Goes,” I assumed, as a fan of Billy Joel and pop documentaries (which tend toward the light and hagiographic these days), that we were going to be in for a punchy, rousing, upbeat behind-the-music Tribeca appetizer. “And So It Goes” is surely an infectious celebration of Joel’s pop magicianship — his indelible qualities as a composer and singer and rock star. And the film worked all too well as an appetizer, since the festival only showed Part 1 of what is, in fact, a two-part HBO documentary.

But Part 1, which is two hours and 27 minutes long, takes you right up through 1980, when Joel has already released his seventh album, “Glass Houses.” So I feel confident in reviewing it as a stand-alone experience. And what took me by surprise is the movie’s emotional gravity. Directed by Susan Lacy and Jessica Levin, “And So It Goes” is not a once-over-lightly, papering-over-the-dark-side portrait of a pop star. It includes a lot of warts, but more than that it shows how Billy Joel’s complicated and not always happy life fueled his incandescent and in some ways deceptively buoyant pop.

“Piano Man,” for instance, emerged from the financial catastrophe of Joel’s early days as a solo artist. To launch himself out of the scruffy demimonde of the Long Island rock scene, he’d secured a contract with the only one interested in signing him — Artie Ripp, owner of Family Productions (who’d gotten wind of Joel through Woodstock co-creator Michael Lang). It turned out to be a deal with the devil. Ripp produced Joel’s first album, “Cold Spring Harbor” (1971), which led off with “She’s Got a Way” (quite a first solo track), but to make sure that the songs fit a radio format, Ripp mastered the album at the wrong speed. Joel also received no money. He moved to Los Angeles and, after drawing the interest of Columbia Records, decided to get out of his contract with Ripp by refusing to perform as “Billy Joel.”

This resulted in his taking a gig for six months at the Executive Room piano bar on Wilshire Boulevard, where he performed standards, billing himself as “Bill Martin” (complete with exaggerated nightclub-singer voice). It was out of this tawdry eccentric chapter that he wrote “Piano Man,” and that’s why the song is great — because you hear the reality of Joel’s experience, his observation of the patrons and the whole piano-man-as-everyman vantage, echoed in the song’s exultant melancholy. There’s a clip of a stadium audience singing along with “Piano Man,” a sea of arms waving in the air, and it’s one of those moments where you feel how deeply that song resonated in Middle America. It made me think back to a Billy Joel concert from 1994, where I saw 50,000 people at the Meadowlands Stadium in New Jersey join together in singing, “A bottle of white! A bottle of red…” I find “Scenes from an Italian Restaurant” to be a grandiose song, but that moment was awesome.

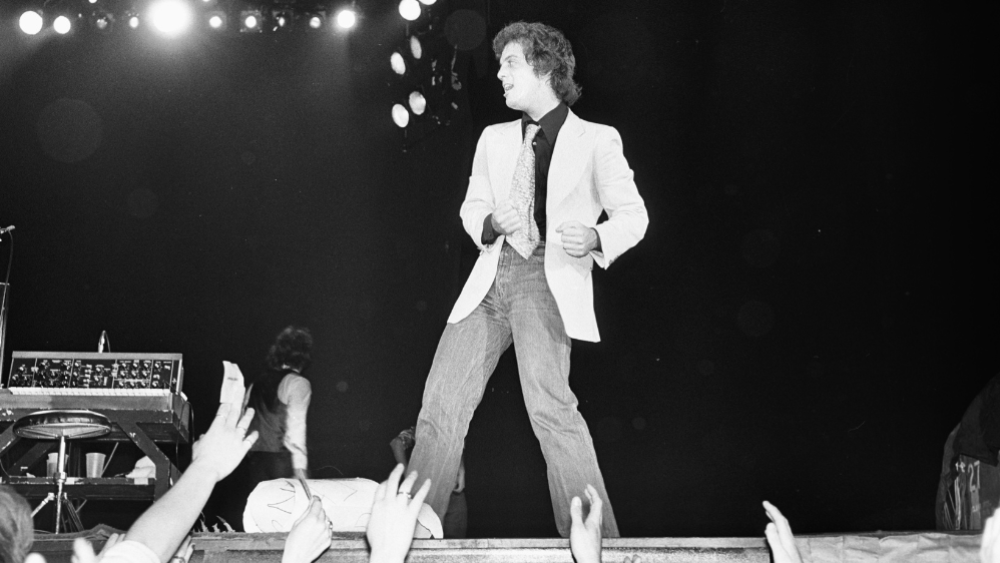

As the documentary captures, Billy Joel arrived as a romantic pop star who was also a pugnacious fighter. You hear that duality in an astounding anecdote he relates about what happened after the release of his fourth album, “Turnstiles,” in 1976. It was an okay but uncertain record, with one song (“New York State of Mind”) that would go on to become a classic, but Joel’s career was ambling along without catching fire. He’d assembled a band of Long Island musicians who felt like brothers to him (sort of like his version of the E Street Band), but he knew he needed a producer who could take him to the next level.

Joel worshipped the Beatles, and like any deep-dish Beatles fan he understood how instrumental the legendary producer George Martin was to their success. So Joel called Martin and asked him to produce his next album. Martin came to a concert to see Billy live, and he was won over. He said he’d produce the record, under one condition: Martin wanted to ditch Billy’s band and use session musicians. It’s not as if this was an off-the-wall idea (session musicians had fueled the splendor of “Pet Sounds” as well as Steely Dan’s albums), but Joel was having none of it. He told Martin: Love me, love my band. And that was that.

Karma then smiled, as that follow-up record, “The Stranger” (1977), was produced by Phil Ramone, who hit upon a mixture of lushness and spontaneity that matched, in its way, what Gus Dudgeon had been doing with Elton John. But when the executives at Columbia heard “The Stranger,” they didn’t think there was one song on it that qualified as a hit single.

“The Stranger” is one of those singular albums, like “Thriller” or “Rumors,” that turned out to be all hit singles. Every song on it is a timeless gem. But radio needed to be convinced, and here’s the weird icing on the cake: Joel’s wife, Elizabeth Weber, who was now his manager, insisted that “Just the Way You Are” be released as the second single (it’s the one that really put the album over), and that was a song that Joel, after he wrote it, didn’t even want on the record. He thought it was too “mushy.” He literally had to be convinced. This is the kind of story that illuminates the mystery of pop.

As a history of Billy Joel’s rise to success, and of how his cavalcade of indelible songs came to be, Part I of “And So It Goes” is richly satisfying fan service. But where the documentary cuts deeper than that is in its slow-burn, almost novelistic portrait of Joel’s first marriage. The way he and Elizabeth got together is out of some Led Zeppelin-haired counterculture version of John Updike. Weber was married to Joel’s bandmate and bosom buddy, Jon Small, when she and Billy fell in love. (She and Small had a son, who Billy ultimately adopted.) For a while, she abandoned both men, which left Joel suicidal. He tried pills and at one point drank a container of Lemon Pledge. But she and Billy reunited and stayed together for 10 years, during which she became his muse and close-knit business partner, inspiring many of his songs (notably “She’s Got a Way” and “She’s Always a Woman”). They had loving and tempestuous bond, and while it’s not as if the film shares a million scandals, co-directors Lacy and Levin catch the saga of the marriage through their delicate use of archival footage, letting us read what’s happening in the couple’s faces. In “And So It Goes,” these pictures are worth a thousand words.

Weber, with a chic wedge of white hair, is interviewed throughout the film — as is Joel, who cooperated with the filmmakers by churning through his life with a refreshing candor. He grew up poor, as a sensitive outsider (the only Jewish kid, and the only kid with divorced parents, in his Long Island neighborhood), and he never even dreamed about being a rock star on the level he became. But he had a look to him, like a cuddly Sly Stallone, and there’s a way that that kind of transformative stardom can’t not go to your head. (That, of course, is what “Big Shot” is about.) The film deals frankly with Joel’s addictions, and how what saved him was probably his obsession with his songcraft.

“And So It Goes” pays tribute to how Joel fused the confessional vibe of the early-’70s singer-songwriter boom with the musical architecture of Tin Pan Alley (Joel’s fellow bridge-and-tunneler Bruce Springsteen testifies that Joel’s songs are built like the Rock of Gibraltar). But the film makes too little a point of one giant forebear. While Paul McCartney shows up and pays tribute to Joel, saying that “Just the Way You Are” is the song he didn’t write that he would most like to have written, the truth is that Billy Joel’s genius for fusing a melodic line with a thought, making it sound like a musical sentence he made up on the spot, was profoundly influenced by McCartney. (John Cougar Mellencamp gets at this quality of Joel’s, as does Nas.) I remember how powerfully that aspect of his writing hit me when I was in a karaoke bar in Key West watching some frat-house dude mangle “I Go to Extremes.” His singing was awful, yet he invested the song with so much passion that I realized, for the first time, what a transcendent song it was. (From that day on, it’s been one of my all-time Joel favorites.)

I can’t render a definitive judgment on “Billy Joel: And So It Goes,” because I haven’t seen Part 2. There are moments when Part 1 does grow a bit repetitive (I wish the film weren’t so doggedly chronological). Yet a day after I saw it, it has stayed with me. Martin Scorsese made a four-hour documentary about one year in the life of Bob Dylan. Billy Joel isn’t Bob Dylan, but he’s a major artist with a 55-year career behind him, and I felt nourished by how this longform film lets you sit inside the irresistibility of his music, and the mighty contradictions that fueled it.