Catchy but Muddled Autocracy Thriller

“Eagles of the Republic” is a Cairo-set political thriller one can slot into the following category: movies about life under autocracy that feel different to watch — at least to Americans — than they would have six months ago. That’s because they hit so much closer to home now. It might sound off-the-wall to describe “Eagles of the Republic” as an “entertaining” saga of repression, but the central character is a fictional Egyptian movie star, and for its first hour or so the film is vivid and funny as it invites us to revel in the perks and gossipy vanity of his charmed but flawed existence.

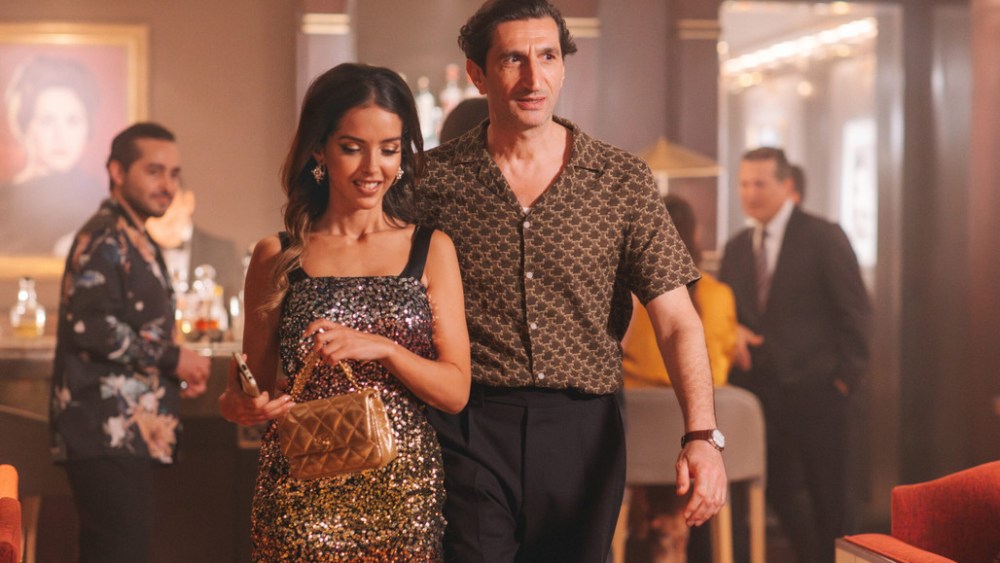

George Fahmy (Fares Fares) is a veteran actor, known as the “Pharoah of the Screen,” who carries himself like the legend he is. He’s tall, with glittering dark eyes and a hawkish profile; he looks like Liam Neeson, with a hint of Harry Dean Stanton’s hangdog melancholy. He’s the number-one box-office star in Egypt, who acts in everything from prestige dramas to films with titles like “The First Egyptian in Space.” He’ll throw his weight around arguing with the country’s Muslim censor board (who never met a movie they couldn’t try to neuter), and his private life is a litany of scandalous privilege. He occupies a lavish apartment and has a mistress, Donya (Lyne Khoudri), who’s half his age and looks like a fashion model. (She’s an aspiring actor.)

George takes what he wants, but there’s a saddened undertow to him that’s not hard to see. Hidden beneath baseball cap and sunglasses, he takes clandestine trips to the pharmacy to purchase Viagra. He is separated from his wife (Donia Massoud) and has a loving but increasingly awkward relationship with his son, Ramy (Suhaib Nashwan), who attends the American University in Cairo. (When the two have drinks and Ramy brings along the girl he’s dating, he has to make sure his father doesn’t hit on her.) Fares Fares is a forceful actor who dramatizes George’s movie-star vanity from the inside out. And then, as he’s gliding through life on his cloud of entitlement, he gets a call asking him to star in a movie commissioned by the Egyptian government.

It will be a biopic about the country’s president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who came to power in 2014 after having staged a military coup. That’s when he toppled Mohamed Morsi, who in 2012 had become Egypt’s first democratically elected leader. (Morsi’s rise was propelled by the protest movements of the Arab Spring.) Sisi, who is still in power, became a textbook autocrat, presiding over a military dictatorship. “Eagles of the Republic” is a saga of life under that regime. We see innocent people arrested for posting a “treasonous” thought on Facebook, and characters perpetually refer to the “they” who are hovering over everything — they meaning the regime. They are not to be messed with.

Tarik Saleh, the film’s writer-director, is of Swedish-Egyptian descent and is based in Sweden, which is why he was able to make “Eagles of the Republic” as an open indictment of life under Sisi. This is the final film in Saleh’s “Cairo trilogy,” after the drug thriller “The Nile Hilton Incident” (2017) and the Muslim clerical-school corruption drama “Cairo Conspiracy” (2022), and for a while it’s an absorbing tale.

When George learns that he’s being asked to star in a piece of state-actioned propaganda, a movie that will be entitled “Will of the People,” he balks. He’s no fan of Egypt’s dictatorship — and besides, he says, how could a star of his look and stature be asked to play Sisi, who is short and bald? But the very fact that he’d raise these objections, in his usual high-maintenance way, indicates that he’s a bit naïve. The Sisi regime isn’t asking George to star in this movie; it’s telling him. As he grudgingly submits to the assignment, getting into his khaki military costume bedecked with medals, we’re pretty certain that we’re going to see a parable of what happens when movie-star hubris runs into the buzzsaw of authoritarian mercilessness.

For a while, that’s just what it is. There’s a man on the set named Dr. Mansour, played by Amr Waked (who’s like a quieter Dennis Farina), and he’s the official who’s there to make sure everything comes out in a way that will be Sisi-approved. Early on he tells George, “You’re giving a bad performance,” and it’s not because he’s suddenly turned drama critic. George’s enactment of Sisi’s rise to power is too exaggerated, too cartoonish — and that’s because it’s George’s way of not giving himself over fully to the role. It’s his way of resisting.

Then George gets invited to a formal dinner at the home of the minister of defense (Tamim Heikal). There’s a group of government higher-ups there, who refer to themselves as “eagles of the republic” — that is, they’re there to survey and protect the nation. But they’re really protecting Sisi and his corrupt rule. By this point George has figured out that he needs to play the game, and he knows how to do it. But when he meets the minister’s imperious wife, the Sorbonne-educated, Western-oriented Suzanne (Zineb Triki), a danger bell goes off. He is soon having an affair with her, which seems a seriously dumb thing to do. We think we know, in our gut, where the movie is headed.

But we don’t. George gets asked to give a speech as a further demonstration of his loyalty, and he agrees. The speech happens right in front of Sisi, at a sunlit military parade to commemorate the soldiers who died fighting Israel in the Yom Kippur (a.k.a. Ramadan) War. George gives the speech. And that’s when something happens. A spasm of violence. There has been a plot against Sisi, in the form of a half-baked military coup, and George is right in the thick of it. He has been used…somehow.

The “somehow” is what we want to know. But that’s where the movie, to our surprise, falls completely apart. Just about everything that happens after the coup attempt is oblique, confusing, garbled, head-scratching. What happened to Saleh’s filmmaking? Leading up to this moment, it was meticulous. Did he leave a bunch of scenes on the cutting-room floor? During the film’s second half, we can piece together what happens (kind of), but not in a way that makes total sense, or that’s at all dramatically satisfying. And yet the movie had been working out such a vital and relevant theme: the stakes of trying to placate a regime of ruthless power. “Eagles of the Republic” loses the thread of its story, but even more disappointingly it leaves those stakes hanging.