Gives You a Contact High

The title of “Cheech & Chong’s Last Movie” makes it sound like another of the duo’s agreeably shambolic made-up-on-the-spot-but-who-could-tell-if-it-wasn’t? buddy-comedy rambles. And given their age (Tommy Chong is about to turn 87; Cheech Marin is a relative spring chicken of 78), you could be forgiven for presuming that they wanted to have one last go at the kind of stoner comedy they invented, a form now as mainstream as the cannabis outlet down the block.

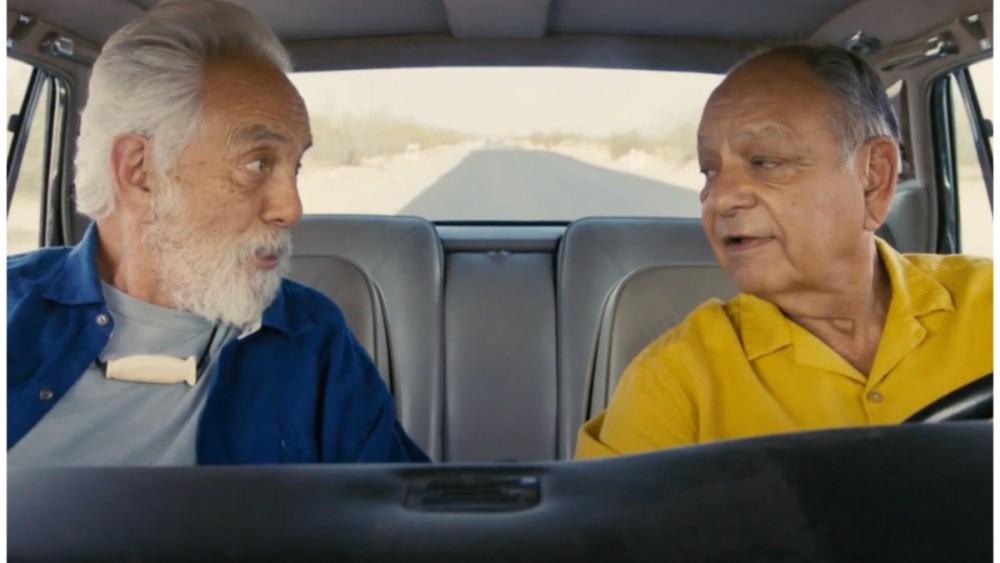

But no, “Cheech & Chong’s Last Movie” turns out to be a straight-up (if not always entirely straight) documentary, a film that takes two hours to trace the life and career of these shaggy comic revolutionaries. We hear about their interesting life stories (Chong started off as an accomplished musician in a group signed by Motown; Cheech was passionate about being a potter), their beyond-random meet-up, the evolution of their act, the way they became huger than huge…and, tying the film together in a rather delightful way, we get the two of them today, driving through the desert in a Rolls Royce with a marijuana-leaf hood ornament, shooting the shit about everything, sort of like Will Ferrell and Harper Steele in “Will & Harper.” Even as we think we’re on a quaint road trip of nostalgia, one that’s probably more scripted than it looks, the two start to bicker and argue about stuff, and the quibbling is real, since it’s clear how much they can still push each other’s buttons, and how that was the hidden spark plug of their act, even though it’s also clear that they still love each other. They’re like the Paul and John of baked idiocy.

I grew up with Cheech and Chong but never counted myself as a major fan of theirs. I chuckled at the first album when I was in middle school, tended to find them likable but also goofy and repetitive, and thought that their movies, after the pretty good “Up in Smoke,” ranged from the overindulgent to the abysmal. Yet given all that, I was surprised to see how won over I was by “Cheech & Chong’s Last Movie.” I’d never spent a minute thinking about how these two put their act together, but the evolution of their career, which took shape with not much more calculation than the comedy bits they often improvised, turns out to be a story at once fascinating and enchanting.

Cheech and Chong often seemed like they were simply meant to be, sprouting up like a random weed plant from the soil of the counterculture. They came along at the perfect moment, reducing the entire hippie world to a burlesque. The hidden joke of their routines — what even a lot of the long-haired druggie types in the audience didn’t quite get — is that the counterculture was over. It was already turning into a parody of itself, and Cheech and Chong just nudged that one step further into doofus-brained insanity.

The two seemed to emerge out of the stoned ether, which is why they gave everyone who saw them a contact high. But it’s not as if they’d set out to be the Martin and Lewis of the hippie-hangover ’70s. The documentary opens with a barrage of clips from their heyday, when they seemed to be everywhere, saying witty and spaced-out things on TV talk shows (Chong: “It’s not hard to see what drugs do to you.” Cheech: “Make you rich!”), spreading their mock philosophy (“We’d like to contribute to the growth of America and the stunting of the growth of America”), while plenty of others were making jokes made about them (Johnny Carson: “Did you hear about the new death penalty? You have to stand between Cheech and Chong for half an hour”).

The movie jumps back a bit to their youth. Chong, whose father was Chinese and his mother Scotch Irish, grew up in impoverished rural Canada, out of which he evolved his borderline Buddhist philosophy: Whatever happens is meant to happen, so deal with it. Cheech grew up in South Central L.A., which was extremely violent. “I saw three murders right in front of my eyes by the time I was seven,” he recalls. He was one of the only Chicanos in a mostly Black neighborhood, and then his father, a tough L.A. cop, moved the family to Grenada Hills in the San Fernando Valley, which was almost exclusively white. All of this informed the way that Cheech, in his comedy, seemed to be playing his funky blissed-out Chicano-everyman character as if he had just arrived from another planet. Which was part of the poetry of it. Cheech Marin was one of the founding fathers of Latino-American pop culture, with a personality so new to the mainstream that he opened the door to everyone from Freddie Prinze to John Leguizamo.

He and Tommy met in Vancouver, where Chong ran a strip club and had a wild life, with two separate families — his wife, Maxine, and with whom he had two children (including Rae Dawn Chong), and his mistress, Shelby, who became pregnant the night they dropped acid together. His lifestyle was made even more fraught when he joined Bobby Taylor and the Vancouvers, who were discovered by the Supremes. Chong cowrote the single “Does Your Mama Know About Me?,” which charted #9 in 1968. But by the turn of the decade, the music life was wearing thin for him, and he became possessed by comedy, running an improv troupe called the Committee out of the strip club. Cheech was hired to cover the troupe by Canada’s equivalent of Rolling Stone magazine, and he wound up joining them. As the counterculture faded away, so did all the members of the Committee…except for Cheech and Chong. But they admit they stole a lot of their classic bits — like the one where they impersonated two dogs — from the troupe.

Cheech and Chong’s career, like their routines, was a perfect storm of happenstance. Just as Andy Kaufman lifted his foreign-man character from someone he had met in college, Chong picked up his whole blinkered “Hey, man!” thing from a homeless Vancouver stoner named Strawberry, and Cheech based his persona on a hitchhiker who could barely keep a conversation going because he was too busy checking out “chicks.”

Comedy clubs didn’t exist yet, so Cheech and Chong, moving to L.A., played the soul clubs, opening for everyone from the Isley Brothers to Ray Charles to the Delfonics. This gave them a unique double vantage. They were comedians of color who were, at the same time, sending up a hippie culture that was mostly white. Then, one night, they played the Troubadour (the place where Elton John was elevated to superstardom in the course of three shows), and that’s when fate struck. Lou Adler was in the audience; he was the fabled record producer who had produced the Mamas and the Papas and Sam Cooke and Carol King’s “Tapestry.” He grew up in Boyle Heights, the Jewish section of East L.A., and recognized the characters Cheech and Chong were doing. They signed a deal with Adler, who had his own record company, in April 1971, and that put them out there.

How they learned to work the recording studio is the most fascinating story in the movie. At first, they didn’t know what they were doing. They had to learn to improvise…within the sonic playground of the studio. When they did, in the sketch entitled “Dave” (though the fans call it “Dave’s Not Here”), the result was magic. Lou Adler had the power to blast that sketch out to radio stations everywhere. And it connected. They were working in the same mode that spawned the Firesign Theater and the National Lampoon Radio Hour, but Cheech and Chong were the exuberantly lowbrow, so-stoned-we’re-dumb, racially aggro, all-appetite version — it’s as if they foresaw the coming Hollywood revolution in how-low-can-you-go comedy.

Their movies, starting with “Up and Smoke” (which Adler directed), made them even bigger stars, though Adler had signed them to such a chintzy deal that though the film grossed $50 million in the U.S. (quite a sum for 1978), they were paid just $25,000 apiece. They cashed in on “Cheech and Chong’s Next Movie” (1980), but in my opinion that was the beginning of the end of their fruitful creative zone — and, apparently, of many of the happier aspects of their partnership. When Chong directed their second feature, it set off a power struggle — and in the desert-ride conversations of “Cheech & Chong’s Last Movie,” it’s clear that they’re still at war about it. Cheech thought Chong became a control freak; Chong admits that he took control as the filmmaker, but says he made Cheech the star of the films. I think both of them miss the real point: that their movies started to suck, and they should have sought out a real filmmaker.

“Cheech and Chong’s Last Movie” has an inspired finale, as the two wind up stranded in the desert, only to look across the road and see a place called The Joint, with a giant smoldering joint adorning the roof. So it’s as if they’d arrived in heaven. Smoking dope was once thought of as a revolutionary activity, a path to “freedom.” It freed your mind from excessive, conventional rationality. Before long, though, it had become just another zoned-out hedonistic middle-class pastime. “Cheech & Chong’s Last Movie” celebrates how Cheech and Chong made comic gold out of the pivot point between those two things. They made us laugh at how we’d all learned to stop worrying and love the bong.