In Defense of Untrained Art

Abiola Oke is a global media strategist and the managing director of ADISA, a global advisory firm focused on entertainment, culture, and brand development. He was previously CEO and publisher of Okayplayer.

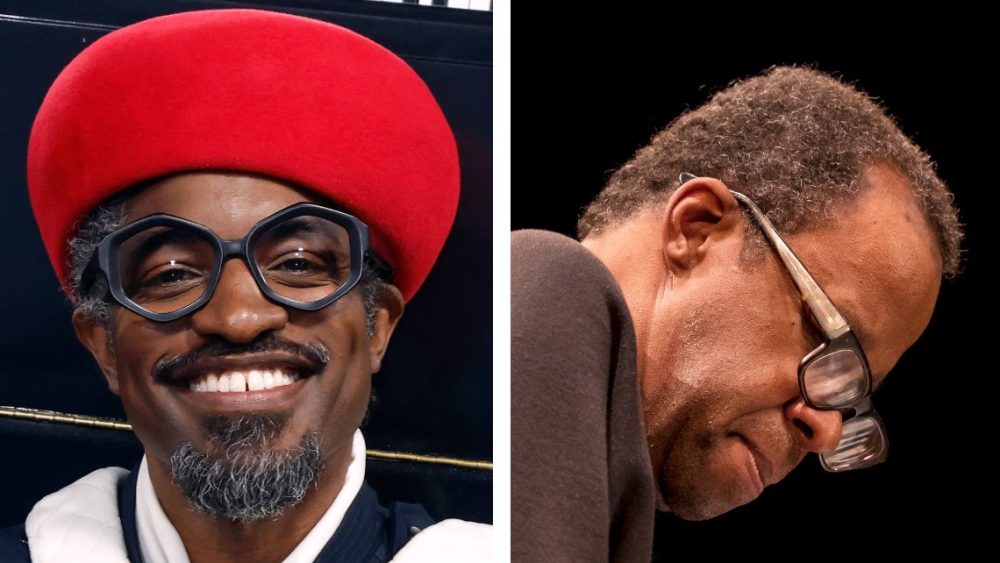

When Andre “3000” Benjamin released an ambient, flute-forward — and Grammy-nominated — work last year as his first-ever full-length solo album, some 18 years after OutKast’s final LP, many wondered what the iconic rapper was chasing. And with the release of a new EP, “7 Piano Sketches” — earnest, unrefined, and entirely instrumental, showing an untrained approach on the piano similar to its predecessor’s with the flute — those questions have returned, with even sharper criticism.

Veteran jazz pianist Matthew Shipp has been vocal in his disapproval. In a sharply worded statement shared on social media, Shipp wrote: “What a lack of respect for the discipline by someone who in my opinion is a complete asshole for doing this – it is depressing that this garbage will get any attention because he has a name and fame – there is nothing refreshing about the naivety of it – it is just downright dreadful and awful – true fucking crap – insipidly wretched nothing.”

From one perspective, his frustration is understandable: Shipp has trained on the piano for decades with the intensity and discipline of an Olympic athlete, while Andre 3000 approaches the instrument with more curiosity than technical skill. And yet, the world at large seems more captivated by Andre’s untrained experimentation than by the hard-earned virtuosity of Shipp and countless other musicians. That dichotomy raises deeper questions about mastery, merit, and the tension between artistic exploration and the preservation of excellence.

As someone who has personally struggled with learning the piano — who understands the labor it takes to achieve beauty on that instrument — I find myself torn. I relate to Shipp’s sense of artistic betrayal. But I also admire Andre 3000’s courage.

This is not a new tension. Plato’s theory of Forms suggests that there is an ideal expression of everything — a blueprint against which all real-world iterations are measured. A chair, in his view, is only a chair inasmuch as it aspires to the perfect form of “Chairness.” By that logic, true art should aim toward its ideal, its highest form. Shipp, in essence, is defending that ideal. His critique is rooted in a belief that jazz improvisation — especially on an instrument as historically sacred as the piano — should not be diluted by amateur experimentations that receive more attention than the work of lifelong craftsmen.

And yet, Plato also made space for the philosopher-artist — someone who stirs the soul not only by mastering the known but by exploring the unknown. Shipp’s criticism, which is not without merit, risks overlooking the creative value of an enthusiastic novice experimenting in public.

Andre 3000 is no stranger to artistic expression, nor does he claim to be a piano virtuoso. He’s a generational talent who helped define one of the most influential eras in hip-hop. His reputation is earned. And when such an artist takes up a new instrument — not to perform flawlessly, but to feel through the keys what defies articulation with words — it’s worth listening, not dismissing. His music doesn’t pretend to be Thelonious Monk. It’s a window into where his artistic spirit is now — curious, reflective, searching.

Some of the melodies on the EP are beautiful. Raw, yes. But alive. And in an age of polished noise, that counts for something.

Part of the reason listeners — and, notably, the press — are so enamored with Andre 3000’s musical pivot isn’t just the sound itself, but the story behind it. It’s like watching a celebrated actor step into a singer’s role, or vice versa — the intrigue comes not only from the performance, but from witnessing someone who excels in one medium take a creative leap, and risk, into another. Some may argue that this kind of attention feels unfair, especially to those who have dedicated their lives to the craft. But it’s not as though the spotlight is really being stolen, because those artists have been prominent in their field for years or decades; what’s changed is that someone with a massive following has entered the space, drawing attention to it. The curiosity and narrative surrounding Andre’s journey became a part of the listening experience — and that, too, is a form of artistry.

Which leads to another unspoken truth: perhaps Shipp isn’t just defending jazz tradition; maybe he also desires a platform as big as Andre’s. The dynamics driving the coverage of Andre’s experimentation aren’t grounded in his skill on the piano; they’re powered by the notoriety he garnered through rap. His presence in any new medium is newsworthy because of that legacy.

Of course, there’s a formidable downside to that logic. We live in an age of creative inflation. With AI and social media democratizing the means of production and distribution, the line between mastery and mediocrity has blurred. In a world where the algorithm doesn’t care how long it took to master a chord progression, story often eclipses skill. Everyone can create — but not everyone is ready for primetime. And audiences increasingly mistake virality for virtuosity.

As it should be, the test lies in the art itself: How does it make you feel? Andre 3000’s piano compositions, though imperfect, feel honest. They resonate not because they fulfill the Platonic ideal of jazz or classical structure, but because they offer vulnerability.

And what if Shipp had chosen to engage rather than criticize in such harsh terms? What would it look like for a jazz purist and a hip-hop icon to collaborate and explore that tension between form and feeling together? It’s easier to tear down from a distance. Harder, but more meaningful, to build something in common.

Andre’s music isn’t an insult to the form, nor a revolution within it. It’s an inquiry. And inquiry deserves room to breathe.

Matthew Shipp has a right to defend the sanctity of the piano. Andre 3000 has a right to explore it. And we, the audience, should resist the urge to pick a side. Instead, we might listen for the harmony between them.