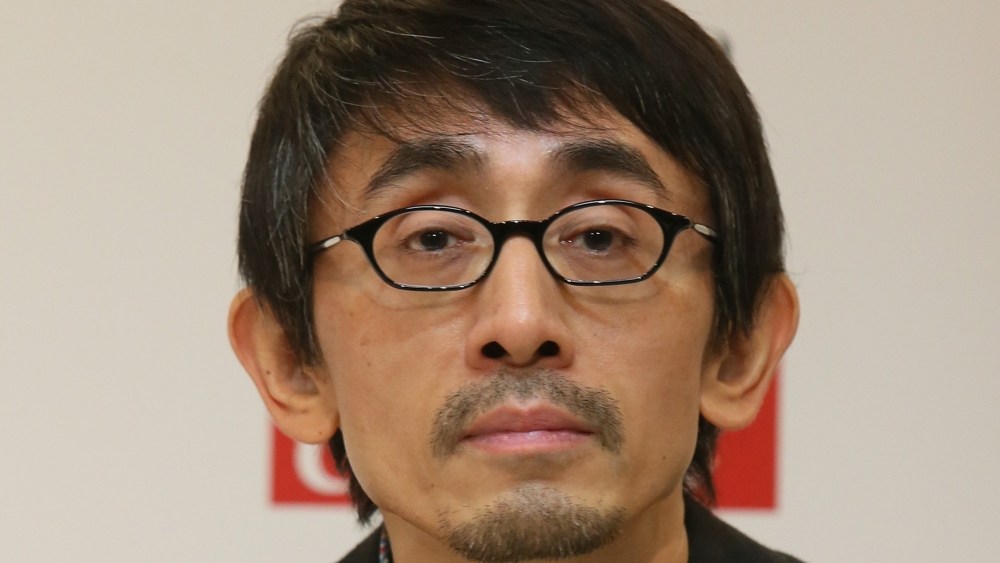

Yoshida Daihachi Analyzes ‘Teki Cometh’

Screening in competition at the 37th edition of the Tokyo International Film Festival, Yoshida Daihachi’s “Teki Cometh” is based on a 1998 novel by Tsutsui Yasutaka about a retired professor, Watanabe Gisuke, who is quietly living out his last days when he receives a mysterious message on his PC that his “enemy” (teki) is coming.

Starring revered veteran actor Kyozo Nagatsuka as Watanabe and filmed in black-and-white, the film begins as a record of his daily existence, from his meticulous meal prep – he is a something of a gourmet – to his platonic relationship with a former student (Takeuchi Kumi) that smolders with an unstated but evident mutual passion.

But once the “enemy” announces its presence, the film segues into darker, more disturbing territory as Watanabe’s unquiet dreams seem to invade his waking life, with his dead wife (Kurosawa Asuka) resenting what she views as his betrayal – and refusing to remain a mere ghost.

In scripting the film, Yoshida said in a pre-TIFF interview, that he updated the novel’s descriptions of Watanabe’s interactions with the digital world – social media has replaced the chat rooms of the 1990s – but Watanbe himself remains what Yoshida describes as a “traditionalist, like the Japanese-style house he lives in.”

His protagonist was a professor of French literature, not exactly a traditionally Japanese pursuit. “He is a symbol of the Japanese who live in a tatami room but drink Coca-Cola, who are always in between Western and Japanese culture,” Yoshida told Variety. “For Japanese people, this stance is very natural and commonplace.”

Yoshida incorporated autobiographical elements into the film, including his depictions of Watanabe’s over-active dream life. “When I was young, I had many dreams that could have been made into movies,” he says, “But as I got older, I had more dreams about things I saw yesterday or worries I had about tomorrow. Then, I got to the point when I couldn’t tell the difference (between dream and reality), so when I woke up, I would think for a while, ‘Oh, what a terrible thing I did.’ I’m having more and more dreams that are realistic in a bad way.”

Yoshida confesses that he detects other overlaps between his life and that of his 77-year-old hero, who feels his world getting smaller even as he tries to find new beginnings. “I turned 60 last year,” Yoshida says. “Before I had been able to work without thinking too much about my age, but now when I start work at 6:00am, I feel a little bit sick. I am also thinking more about what I should do in the future, not only for work, but also for how I should live my life. This is true for not only me, but also the Japanese people as a whole. There are more and more old people around me, and the number of children is decreasing. That makes me feel uneasy.”

So, when Yoshida reread Tsutsui’s novel after an interval of years, its story of an elderly man trying to restart his life while pursued by his past struck him as timely. “I thought its theme was a good one for me to work on,” he says.

He did not, however, make “Teki Cometh” to impart a message about the present moment. “I really like the feeling that the audience is active and engaged,” he says. “So, I hope this film can establish that kind of relationship with the audience. Not one-sided, but more like a dream that you interpret with you own imagination. A dream that you want to dream again.”